Securities Law & Crypto: fundraising mechanisms and the accredited investor standard

The original version of this post appeared in the October 11th, 2018 edition of Messari’s “Unqualified Opinions”.

The TLDR of this post is best summed up by the following tweet from Benedict Evans:

Now…let’s talk about fundraising + the “accredited investor” standard…

Recently, I have seen a ton of online discussions (mostly criticisms) around the “accredited investor” standard in private fundraising. I’ve also seen people talking about how easy it was to forge documentation on various KYC platforms in order to “get around” the requirements (for the love of god you guys please don’t brag about that on a public forum or social media channel).

This post is not necessarily meant to take a stance, but rather, to provide some nuanced context for the private fundraising marketplace, requirements under the accredited investor laws, and how the trend towards crowdfunding could frame some of the rethinking around those requirements.

📚 A crash course in registered & unregistered securities offerings.

As a general matter, every single offer and sale of a security is required by US federal securities law to either 1. Be registered with the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC); or 2. Be able to claim some exemption from that registration.

In other words: A company or private fund may not offer or sell securities unless the transaction has been registered with the SEC OR if an exemption from registration is available.

A little more background on each of the two requirements:

In order to properly “register" a security under the Securities Act (this refers to the Securities Act of 33, which is just one part of federal legislation that the SEC enforces), a company would have to file for a S-1 registration statement (or what’s commonly known as a prospectus), which, among other things, will ask for things like— risk factors, use of proceeds, plan of distribution, description of securities. The S-1 form also asks for financial statements and other relevant information from (Example of a S-1 form is here: https://www.sec.gov/files/forms-1.pdf)

Current federal securities law allow for companies or private funds to fund raise (aka accept money) without having to register with the SEC, as long as these companies or funds can rely on an exemption to registration. These exemptions have been around for decades, but the 2012 JOBS act notably signed or amended a couple of them into existence: Regulation A (effective as of June 19, 2015) , Regulation Crowdfunding (May 16, 2016) , Regulation D 506 (c) (effective as of September 2013). These were mostly intended to make it easier for small businesses to raise funds from more investors. Obviously, there are different requirements for each of the rules— ex. limited fund size, accredited investor status, etc.

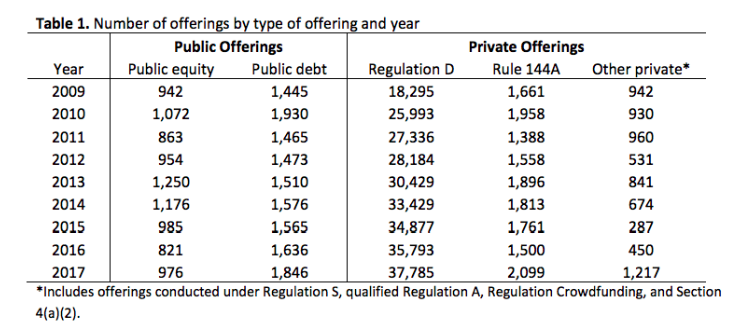

Without going into too deep of the dumpster fire of securities law details, here is the main point: the increasing trend that we are seeing in the capital formation marketplace is the skew towards the unregistered offerings (those that fall within the second bucket) market. In 2017, the total amount in the U.S. raised through all private offering channels totaled over $ 3.0 trillion USD. Meanwhile, the U.S. has seen a steady and significant decrease in the number of public reporting companies in the U.S., particularly since the dot com crash and implementation of the Sarbanes‐Oxley Act.

Source: sec.gov

Why are we seeing the decline in public offerings? Well, the process of actually being a securities public offering (for example, an IPO) is a long and difficult process for most companies. The paperwork + legal/ audit/ accounting fees, and the constant maintenance for doing so turn a lot of small companies off that path. PLUS— if you issue or sell your securities under something like Rule 506, those are considered “covered securities” and are exempt from state securities law registration and qualification requirements. It is much easier for a company to raise money through other ways instead of an IPO.

And…this is where companies (especially with the boom in the number of startups) look to those exemptions to rely on— and raise money that way. Since the JOBS act, we have seen a number of banks of deregistering (relying instead on private or example offerings to raise capital), and companies are choosing to defer their IPOs (relying instead on private financing). Example of high profile pre-IPO private placement include the likes of Pinterest, Uber, Spotify, Palantir, etc.

🕵🏻♀️ So what exactly is an “accredited investor”, and why are people so worked up about it?

Currently, in order to qualified as an accredited investor, one must meet the following requirements:

Have a net worth of at least $1 million (excluding value of primary resident), OR

Have earned income that exceeds $200,000 in each of the prior two years— and can expect the same for the current year (or, together with a spouse, $300,000)

Let’s dial this back for a second. So— for of the uproar over “accredited investor” only funds, it really is Rule 506 (c) that only accepts accredited investors. Given that there are a number of other options and rules for companies to rely on, what’s the big deal?

I’M GLAD YOU ASKED.

Rule 506 (c) sits under Regulation D, which in total accounted for 1.8 TRILLION dollars raised in just 207 (remember that the entire market for unregistered securities offerings in that same year was around $ 3 trillion dollars). To put this into perspective, the amount of money raised via Regulation D is considerably larger than the amount of public debt (straight and convertible debt) AND public equity (common and preferred) offerings over the same time period.

The problem is— over 99% of that Regulation D money is raised through Rule 506, which is pretty much the only rule that is the most inflexible when it comes to letting non-accredited investors invest.

Source: sec.gov

Basically, if you cannot meet the above requirements, then you are excluded from investing into any companies that are raising their money via Rule 506 (c) (or, god forbid you become the 36th person to want to invest in a company replying on Rule 506 (b)!)

Seeing that Reg D offerings are those that raise the most money, but are also the most limiting in terms of who is allowed to invest, there has been a lot of (very understandable) frustrations, which boils down to this: why should how many money you own dictate what you are, or are not, allowed to invest in? The $200,000 income number seems super random, and the $1 million net worth seems laughably out of touch to the majority of the population.

🤷🏻♀️Protecting investors: some practical observations...

Some people have criticized how “easy” the verification process for accredited investor status is on the various platforms that offer KYC services and the like, and while it is true that you can easily manipulate screenshots or images in order to circumvent the requirements for investing, this by and large misses the point of the accredited investor laws.

The accredited investor standards are laws that are meant to protect the *investors*, not the issuer. As a result, the burden and responsibility of the status verification process falls on the shoulder of the issuers of the securities. The issuer has a responsibility to demonstrate that they did their due diligence (there are different thresholds depending on the rule relied on for registration exemption, which I will not bore you with!).

So, misrepresenting your own investor status means it's most likely the company/issuer that gets screwed at the end, because that then destroys their ability to rely on something like, 506 (b) or (c) to fund raise. (Not to mention that it’s likely illegal to forge government issued identification documents to begin with…)

Basically: no one is winning when documents are forged. Unlike scoring an ID from an older sibling when you’re still under 21, it’s not something to really brag about.

🧠My brain is melting…

Almost done.

A lot of token sales— especially this year— have taken the route of a Regulation D offering in order to comply with securities law.

It’s a good thing that more issuers are being cautious / thoughtful with the way they raise funds, but it also seems somewhat antithetical to crypto’s entire ethos, which is to build towards an open financial system, and level the playing field for everyone regardless of income or wealth.

To be fair, I get it. Raising money under something like Reg D is super easy, because you don’t really need to disclose any information about your company aside from a four page form. And because the entire SEC exists pretty much to ensure investor protection, it is really hard to figure out how to minimize harm done to investors in the private funds ecosystem while also letting companies raise money in a way that is easy for them. So setting an income or net worth level seem to be a good idea, since the assumption is— if you can make money, you probably know things (lol).

There have been some suggestions in D.C. to solve this issue. This summer, there was a bill that was introduced in D.C. that proposed to consider someone’s “qualifying education and experience” to determine that status. From the discussions I have seen, people seemed to agree with this move.

My issue with this is two folds: 1. Who is to determine what is enough as "qualifying education”, and 2. how will that be tested and standardized? Eventually, I can see the same critique around this set of standards, which is: why should my degree be the sole determinator of how qualified I am to make an investment? Furthermore, how will you measure someone’s experience—issue a standardized test? That also seems to me to have some unintended circumstances. For example: some people aren’t great test takers, why would a test score be the sole determinator of how qualified I am to make an investment decision?

I’ve talked to some people around me who have suggested other solutions, but they all seem to be limiting in their own way.

🤓 I’m done, I promise…

Token sales have introduced a new form of fundraising—or more specifically, a new form of crowdfunding. But due to the legal and regulatory considerations, token teams are falling back on the traditional private fundraising model—an outdated and arbitrary one that shuts out valuable potential network participants, but a devil that’s at least well known.

I’ve barely scratched the surface, but I’ll stop to give you a breather.

Reminder: I’m not barred in any U.S. state and this is most definitely not legal advice (hire your own counsel pls!), but I do hope these ramblings from a huge legal and policy nerd shed more light on a much discussed, but little understood process.

As always, if you’ve made it this far in my ramblings…you are the MVP.